Career transitions & working identity pt. 2

Mimetic desire, Jonah & the whale, and the unanswered Call to Adventure.

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

- Carl Jung

It’s somewhat ironic that my last post, titled ‘Do Nothing’, extolled the virtues of rest and inactivity. Over the past weeks, life conspired to make me take my own prescription.

Just over a month ago, I showed up to a Monday morning meeting at a startup I’d joined early this year. The meeting proceeded as normal. Only a few seconds after the call ended, my bosses called me and informed me that my contract was being terminated. The call didn’t last long. In the minutes that followed, I felt crushed. Disappointment wasn’t the only feeling, however. Slowly, waves of quiet relief started to wash over me. There was a degree of inevitability about all this. In the minutes and hours that followed, what I needed to do next became clearer. I decided to take some time off to pause, rest, and reflect…

This is the first time in my life I’ve truly experienced a ‘failure’ in conventional terms, and in a somewhat more brutal form. Everybody I talk to about this has been kind and supportive. A friend’s message this morning captured what everybody, in essence, seems to say:

“It wasn't that you weren't right for the job, it's that the job wasn't right for you.”

There may well be some truth in that. But does the fault lie in our stars or in ourselves? I believe I owe myself and others an audit of the decisions and thinking (or lack of it) that led me to this point.

I’ve written about career transitions and working identity in an earlier post, in which I described lessons I’d extracted from my professional journey. The ending of that post appeared to suggest I’d gone through a liminal stage and made it through the other end, having accepted a new job offer after a five-year stretch at one organization. Reading to the end of that post, one might assume it was a happy ending. Instead, as I’ve realised over the past month, I’m still very much in a liminal stage, the metaphorical belly of the whale, exploring different possibilities and experimenting with different hats.

One of the shortcomings of the culture we live in is the myth of arrival: our personal highlight reels almost exclusively broadcast our successes, moments of triumph, of consolidation. A more honest rendering would treat our lives as a gradual, continuous unfolding, punctuated equally by these heady peaks as well as the more messier troughs of loss and struggle. Talking about our personal unravellings isn’t sexy, but it’s necessary in order to let people know the truth: even what we regard as conventional success stories aren’t linear. I’ve found that hearing about the rougher, more jagged periods in other people’s lives has helped me far more than hearing about success. Such accounts are honest, raw, real, and more likely to acknowledge the role of luck, chance, randomness and circumstance. Being let go from a job was a painful thing I’d never expected to experience. But it has also led to some important realisations, a heightened degree of self-awareness, and, hopefully, a return to core motivations that will drive the next stage of my life.

It’s hard to admit that much of my earlier successes were predicated on nurturing, kind environments, patient, understanding, and mature bosses, co-operative colleagues, and the affordances of relative independence and autonomy. In an environment that didn’t allow me these affordances, the tide ran out quickly on me and my personal narrative. Realising that my past success was connected with everything else and is not my own, allows for a degree of grace I haven’t experienced before.

I’m sharing the story of how I got here in the hope that it will encourage more honest accounts of our lives, at work and elsewhere.

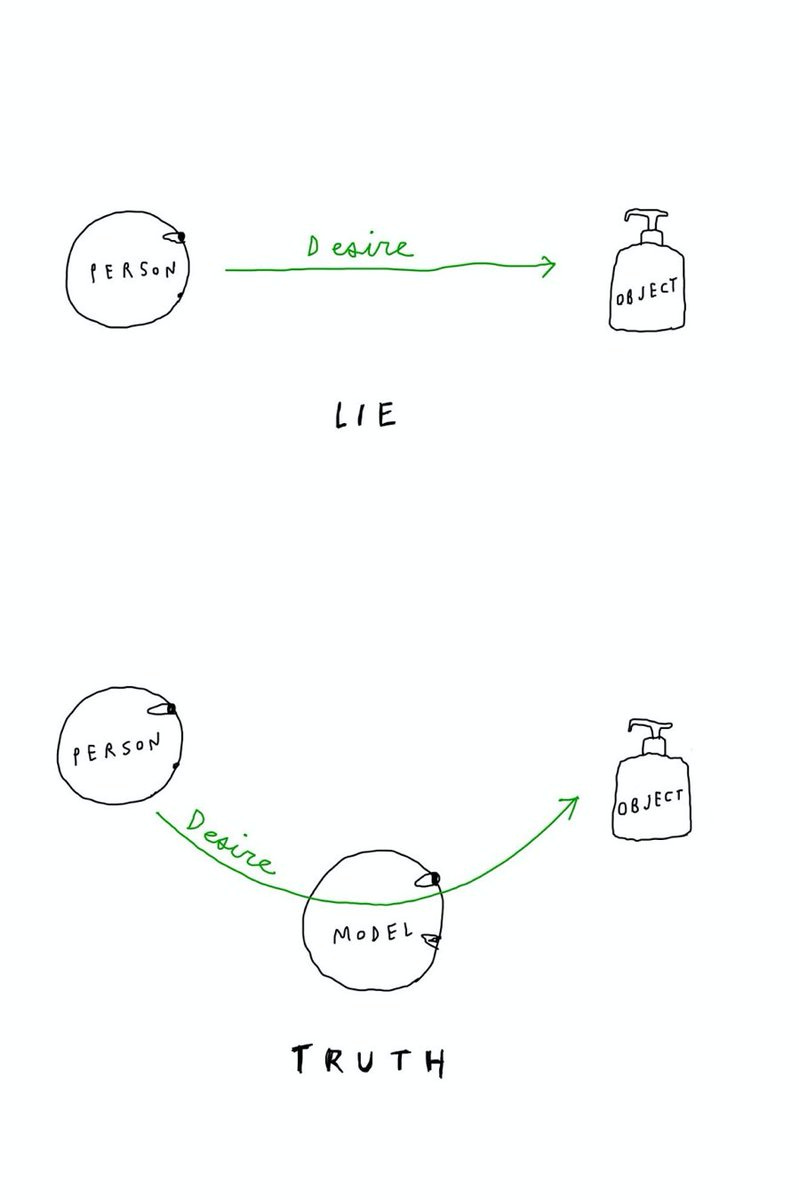

I read Luke Burgis’ Wanting earlier this year, an accessible distillation of philosopher René Girard’s theory of mimetic desire and its role in human society. Put simply, our desires are often not the original things we see them as. That we think of them as being born from within us is the ‘Romantic Lie’ we tell ourselves. Instead, they are modelled for us by other people, and the things we want or do not want are often a reaction to the way they’ve been modelled for us.

“The Romantic Lie is self-delusion, the story people tell about why they make certain choices: because it fits their personal preferences, or because they see its objective qualities, or because they simply saw it and therefore wanted it. They believe that there is a straight line between them and the things they want. That’s a lie. The truth is that the line is always curved.” - Luke Burgis, Wanting

Parents are powerful models. My parents both worked in journalism. It’s not entirely surprising, then, that they modelled particular things for me growing up: an appreciation for literature, reading, writing, and maximal use of my verbal faculties. I once recall being asked who my career inspiration was, and I found no hesitation in saying it was my father. There was no question about it: his work ethic, his excellence on the job, his positive influence on other people, the experiences his job availed him - all of these things in turn influenced me. As I grew older, my parents encouraged me to write. My father would often would take me along with him to work events, where I saw him on the job, meeting important, influential people. Work was clearly the centre of his life, as it is for most people. It was inspiring to me that my father often equated work with fun. I’d even found these lines in his diary:

Rest is not quitting

The busy career;

Rest is the fitting

Of self to its sphere.

That particular notion of work as a central part of life, as play and fun, modelled for me for so long, was what I wanted for myself.

So, years down the line, having been singled out at school and college as having a knack for writing and editing, I decided that financial journalism was a good starting point for me: an approximation that combined my interest in business and finance with my skills at writing. My parents were supportive. But of course: parents tend to project their success on to their children. It’s natural to believe that what worked for them may work for their kids too, and so they extrapolate the things they did as being viable paths. Of course, things change. Forty years ago, when my parents first entered the workforce, the Internet and knowledge work as we know it today didn’t exist. The social contract they inhabited was different.

Little did I know when first I hit the floor of a newsroom, how journalism had changed from their time and how different the current reality was from my expectations. I wasn’t prepared. As a trainee in my first journalism gig, I floundered from desk to desk, and received middling reviews from most of the teams I’d worked with. It was pure luck that a colleague recognised my USP: working with graphics and data. He encouraged me to keep at it, and eventually, leaning in to my strengths, I managed to craft a niche for myself at work. People appreciated my work and my contributions, and I was quickly rewarded. Recognition also followed: I was nominated for an award.

But mimetic desire struck again.

I started comparing myself to other people: people with privileges that far exceeded my own at the time. Why did I not get that promotion or transfer? How, and why was so-and-so rewarded and not me? Why wasn’t I allowed to grow in the direction I wanted?

In his book, Burgis distinguishes between thin and thick desires.

“Thin desires are ephemeral, fleeting, and highly mimetic. They come and go. Thick desires are the ones you’ve probably been cultivating your whole life, but they are usually buried beneath a pile of thin, ultimately unfulfilling, wants.”

- Luke Burgis

Some of my desires were thick: legitimate and true to my core motivations. I wanted to learn new things, take on new challenges, and deepen my skills. But at the same time, there were more shrill, thin desires: I wanted more pay, more status, and more prestige.

I got greedy, and grew entitled. I started to believe in my own success, quickly forgetting the very conditions that created it.

“But 'tis a common proof,

That lowliness is young ambition's ladder,

Whereto the climber-upward turns his face;

But when he once attains the upmost round

He then unto the ladder turns his back,

Looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees

By which he did ascend.”

- Brutus in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Going into the pandemic, my team underwent a reorganisation that took me far away from the nurturing context that had enabled my ascent from directionless, “laid-back” trainee to Young Financial Journalist of the Year nominee. Under the new setup, I was suddenly a nobody. A more shrewd person might have seen the impending reorg coming and realigned themselves with their new bosses. In my conceit, I disregarded the new management and clung to my past achievements, insisting that I be rewarded with the growth I wanted, even though it was clear that none of that mattered a shred in the new context. Naturally, I was ignored.

What’s more? The new context made it ever more clear to me that I was a misfit in a newsroom. So, I gave in to mimetic desire again - I abandoned my unique role and tried to do what everyone else did: pick a beat and cover it. I found, quickly, that my results were mostly mediocre. While I’ve always paid attention to trends, my exploratory attention has never quite overlapped with what most journalists or reporters would consider to be news. I ended up being terrible at pitching story ideas, mainly because I’m wired to focus on perennial knowledge that has longer shelf life but not information, which changes more quickly. But I learned, much to my chagrin, that my approach was the very opposite of how the news business works. Add to that the current business environment, the decline of the media industry, and the perverse incentives, and I realized soon that only ideas that align with those incentives, ones that convert to a high valence headline, could make the cut. And while I may have had good ideas, I was still poor at selling them in the manner that would make a news editor’s ears perk up.

When I got the chance to make a move, I jumped at it: a role related to news, but in a different industry that was grabbing the headlines (mimetic!) at the time: crypto. Despite taking this detour, I never really let go of my identity as a journalist. Being something was better for my ego than being nothing. What would letting go of this identity mean? I didn’t know, and I perhaps didn’t want to think about it. In my new iteration as a news content editor, I carried my old context with me. I focused on trying to do real news, even though the job was primarily geared around business and marketing objectives. Instead of leaning into the new environment and being patient to see what emerged, I gravitated towards what I knew, and jumped eagerly at any opportunity that resembled familiarity and gave me a sense of competence. I was unwilling to sit with uncertainty, with ambiguity, and to allow time for truly creative ideas to percolate. I was in a new context, with new requirements, and new challenges. Instead of trying to lean in to the new, I fell back on the old and familiar. Worse, I even tried to assert it as much as I could: uncertainty and ambiguity have a way of making the ego assert itself in a stronger way than usual. The environment in which I was operating didn’t particularly help either: I thought I had escaped the consequences of the reorg at my previous firm only to go through three more at the new company during the course of a single year. Having to impress a new boss and justify my job every few months proved exhausting. I lost motivation and started to slide. It was noticed. I was called to a meeting in which my boss carefully unpacked all of my shortcomings and slip ups, and was very kindly told to improve. I addressed each of those items, and things were starting to look up. But I was still unsatisfied: something was missing. A sense of vitality, doing something that matters.

While on a holiday, I was contacted by a recruiter. The opportunity sounded exciting: a news startup funded by a well-known brand in the same industry. I was looking for something engaging, something that would make me come alive. Perhaps this was it. I was also being offered a chance to live out the wider culture’s mimetic notion of success: porting one’s experience to a startup with the potential make it big. Carried away, I did not do enough due diligence. I should have been careful and persistent about trying to nail down a specific role and calibrate my hiring team’s expectations. Instead, I was swayed by the brand and how my interviewers flattered me. Friends cautioned me. My partner questioned my decision-making. I flip-flopped over the decision for a week. Even if not an ideal fit, my job at the time offered a degree of stability and slack for me to pursue my interests on the side. But I convinced myself: I needed to prove to a certain set of people that I could work as a journalist. Perhaps this was it, the moment when it would all come together. I just needed the right opportunity, I told myself. But it was just a desperate bid to inject some excitement and vitality into my life and pursue a path unsuited for me. I was right in chasing a sense of vitality, and wanting to be useful. But I sought it out in the wrong place and for the wrong reasons.

Ultimately, what I really wanted bubbled up to the surface in a way I didn’t expect.

I’d been mulling taking a break for some time: 10 years, to be precise. I first wanted to do that by taking a gap year after college. But amid the mimetic job seeking frenzy of my final year, I ended up applying for, and taking a job. Since then, my early twenties, I’ve been working non-stop, with the exception of two years spent in graduate school from 2014-2016. Then, after working for a five-year stretch at the same organisation, I changed jobs twice, with not more than a week’s break in between each role. That was a mistake.

Three weeks into the new job, I told the company that I wanted to quit. I wasn’t a fit, and I knew it. While they encouraged me to carry on, I knew I’d already shot myself in the foot. I’d already told them what I wanted. One of my favourite writers, Tom Morgan, recently said:

“My biggest concern with manifestation is not that it’s bullshit, it’s that it works.”

What we want and how we feel leaks and bleeds into our interactions. Every morning, I’d wake up a ball of anxiety, scrambling for ideas, scrambling to get my thoughts together so I could sound coherent to this new group of people I was working with. Every day was a struggle to justify to myself and others why I was doing what I was doing. Eventually, I must imagine they realised I’d already told them what I wanted, and they gave it to me by letting me go.

It couldn’t have been coincidence that days later, I came across Jordan Peterson’s telling of the story of Jonah and the Whale in the Bible. I felt my experience over the past month resonating strongly with this story.

God tells Jonah to go to sin-city Nineveh and tell the people to repent. This is the archetypal Call to Adventure in Joseph’s Campbell Hero’s Journey, which Jonah ignores. Instead, he runs away and boards a ship headed elsewhere. The ship gets caught up in a terrible storm that threatens to break it apart: that’s the Call getting louder, as one continues to ignore it. The ship’s crew draw lots and conclude Jonah is the cause of their predicament. Jonah then tells the ship’s crew to throw him overboard: he believes the storm is God’s doing and retribution for his actions. The crew is reluctant, and continue rowing to no avail. In the end, however, they’re forced to throw Jonah overboard. The storm abates.

Meanwhile, Jonah is swallowed by a whale, and he remains in its belly for three days. He prays to God and is eventually spit out on to land. Jonah then proceeds to his assignment at Nineveh, his destiny.

As for my personal journey, I believe I’m still in the belly of the whale. But if this recent experience is anything to go by, I believe I’ve made some progress by finally answering a long-standing Call from my body and mind: giving them rest.

More about my time off soon.

Thanks for reading!

Ritvik