Career transitions & working identity

A personal case study

I was recently invited back to Goodenough College - a truly one-of-a-kind postgraduate residence hall in London - to give a talk to business students. I spent a happy year as a resident at Goodenough while pursuing my Master’s degree five years ago. I’ve maintained a steady relationship with the place since, and I never decline an opportunity to visit.

Those of you who read the first edition of this newsletter may recall I referenced Dan Romero’s excellent compilation of readings on crypto. Among those, was a piece called ‘The Slow Death of the Firm’ by Nick Tomaino, which talked about the emergence of decentralised organisations. I’ve found Elon Musk’s description of a company as a ‘cybernetic collective of people and machines’ compelling and I thought 2020 threw this idea into stark relief. I also started reading The Sovereign Individual, and I was quite impressed with how prescient its predictions - made over 20 years ago - were about the times we’re living in now. I also read Lynda Gratton’s The Shift, which dealt with the future of work (Perhaps I’ll start doing posts where I put up book summaries/lessons or key takeaways).

I first thought about stitching all the different ideas and themes I encountered in this material together in my talk to this group of business students. But I realised: these people are all in school. They probably get enough folks talking to them about these types of things. I did not want to come across as yet another academic. I’ve been taken by the power of myth and stories lately. Stories convey implicit, complex truths about the nature of human life and embedded within some are implicit instructions for how one might live. So I thought I would share my career story while trying to extract some of the guiding principles, or implicit truths I discovered for myself along the way.

I’m glad I went with that decision: a number of people approached me after the talk to tell me that what I conveyed was relatable. It was also the first talk I gave in which I barely consulted my written notes. In the past, I would usually write my entire speech down to every word and have notes handy. This provided the two-pronged advantage of not having to rely on memory while simultaneously emphasising delivery. This time round, I somehow didn’t feel like doing that. I felt I was past the point where I wanted to elicit superficial responses like applause or laughter. Given that the material in this talk was within the comfortably familiar contours of my own story, I wanted to use this as a chance to speak (and think) in real-time. There’s something nerve-racking yet engaging about speaking extemporaneously: it anchors you in the moment, while affording you the chance to refine your ideas in the present, choosing words and descriptions appropriate to your thoughts and feelings. It’s not forced or affected. It’s…embodied.

The invitation to give this talk came at an opportune time. I’ve just been through a career transition - I changed jobs two weeks ago. I’ve also just turned 30. So it’s been a good time to reflect on my journey so far.

This post is essentially my talk in written form. The added benefit of this format means that I don’t have a limit on word count or time, and I get to add in reference material for you to explore.

Here goes:

I grew up in a home in which both my parents worked as journalists. My mother spent the bulk of her career as an editor and my father as a reporter. That meant I grew up around books. My folks got me into reading early. Alongside the reading, I was encouraged to write. As early as fifth grade, I contributed an article to my school’s student newspaper, which I eventually became the editor of. Even at university, I ended up editing my college newsletter and producing its yearbook. I started a department-wide newsletter in my first job. And I eventually ended up working in journalism. I never felt like writing or editing was work. I automatically gravitated towards these activities. This almost unconscious affinity for reading, writing and for expressing ideas with delicacy has manifested throughout my life.

And so that brings me to the first lesson I learned, which is:

That sounds simple. Simple, but not easy. There are many things that compete for our attention. Devices and social media are today’s obvious lures, but the overall culture in which we live also exerts a force on our attention, directing it in ways we may not fully be aware of. By paying attention, I mean observing yourself and the things you gravitate towards. Pay attention to weird things happening around you. Pay attention to things that you’ve been doing for a long time, things that have become second nature to you, things that feel more like play than work. You’ve probably experienced a distinct sense of being alive and energised when you do these things.

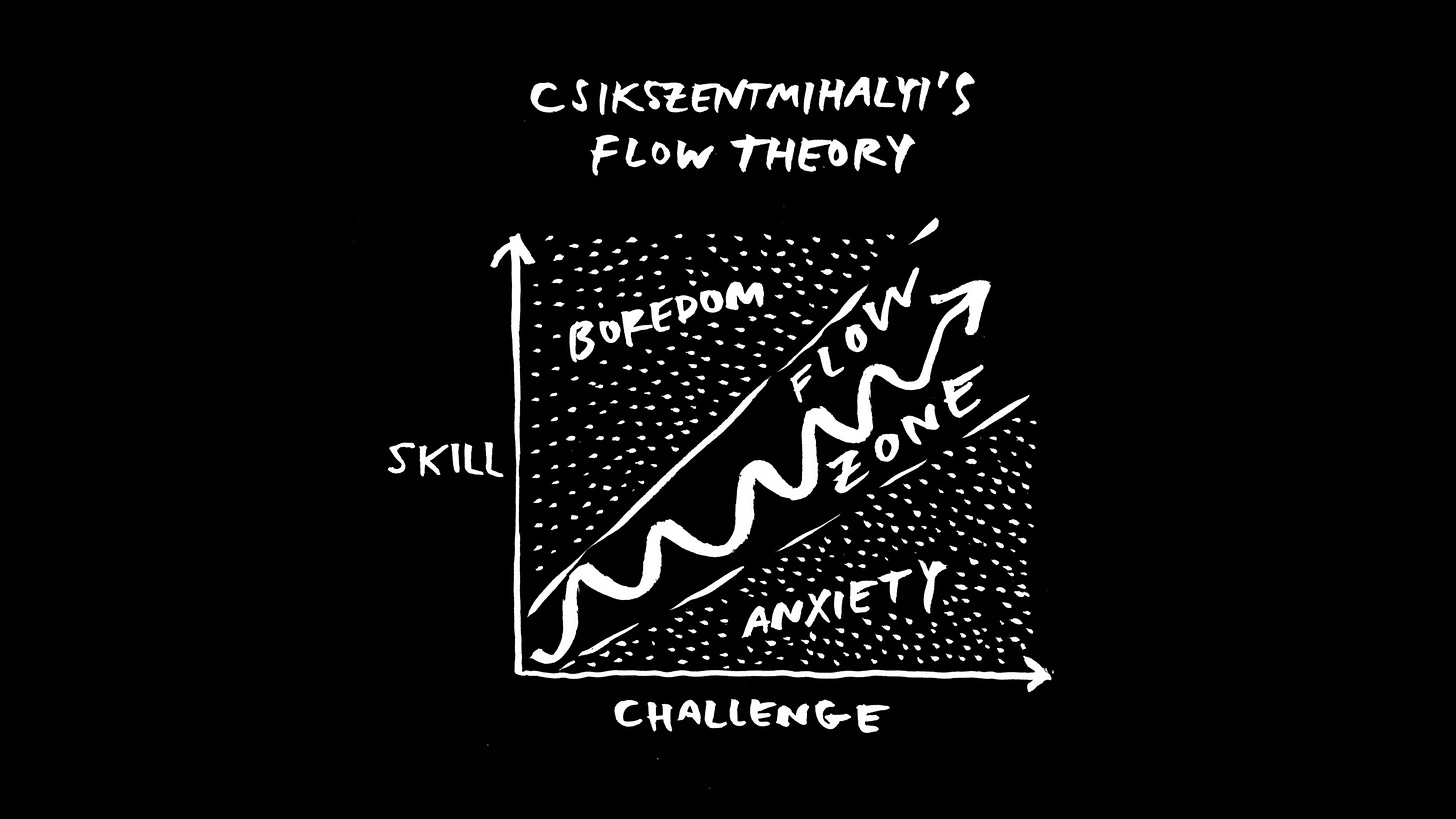

I’m talking, of course, about the experiences you’ve had that produced the flow state, first named by psychologist Mihaly Czikzentmihalyi, who passed away less than a month ago (Austin Kleon wrote a short, sweet tribute to him here).

A flow state, also known colloquially as being in the zone, is the mental state in which a person performing some activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity. In essence, flow is characterized by the complete absorption in what one does, and a resulting transformation in one's sense of time. - Wikipedia

All kinds of experiences can produce flow, but it’s also an incredibly elusive state to achieve in a world in which attention is increasingly fragmented. Paying attention to flow experiences when they occur is important because they give us a sense of where our primal inclinations lie. We have different sets of intelligences that interact with the world in specific ways, constantly giving us feedback about what we enjoy or do not, or what works for us and what doesn’t. Of course, in order to be able to do this, it’s important to build your capacity for paying attention.

Back to my story. Discovering the idea of flow helped me make sense of the feeling I got while reading and writing. I decided that if I were to work, I would try to design my life in such a manner that I maximise my lifestyle and career for flow experiences. How cool would it be to get paid to read and write everyday? But life isn’t so straightforward. As I said, a lot of things compete for our attention.

At the time, proving myself to other people mattered. I’d always been interested in business. My parents often discussed business and economic issues and my father was a business reporter for the bulk of his career. Having taken a business track in high school, I decided to study accounting in college. Going to business school for undergrad meant that I was influenced by the expectations and aspirations of people around me - nearly everyone I knew were taking jobs in the corporate world. I felt at the time that my literary aspirations were something I could always pursue, or pursue later. I wanted to explore and try something new, out of my comfort zone. Curious about the world of finance, I ended up taking a job in the back office of a secretive Wall Street hedge fund.

Now, my first job barely involved any writing. But again, it’s important to pay attention. I found myself reading a lot online, at work, at home, and I somehow found writing emails at work oddly satisfying. Perhaps it was the only expressive outlet I had in that job. My boss at the time also commended my communication skills in a performance review. After a point though, I grew increasingly bored with the day-to-day work. Although I worked at this excellent firm with great people, I quickly saw that the only thing that would grow in 5 years would be my body fat percentage and my paycheck. So I left. But not before going through another process which led me to doing what I did next.

I applied for a job at a news agency. I got invited for an interview, and subsequently a test. I remember having something of an epiphany (in my head, it felt like the heavens parted and a light shone through) when I was called into this office to do this test. It had all these questions about finance, stock markets, and one of the question prompts asked me to write something. I recall feeling a sudden, unexplained surge of excitement, a sense that this is where I needed to be, or the path I needed to take. It felt like my intuition was tugging at me during that one hour, telling me something.

Here’s Joseph Campbell’s exhortation to follow your bliss:

“We’re having experiences all the time which may on occasion render some sense of this, a little intuition of where your joy is…Grab it! No one can tell you what it’s going to be. You’ve got to learn to recognise your own depths.”

I felt like if this writing test represented even a bit of what the job was like, then this was a kind of work I’d like to try. It seemed to be an ideal meeting point between something I thought I could do competently - writing - and my interest in business. I didn’t get the job. But I knew where I needed to go next. I decided that I would go to journalism school, specifically for financial journalism.

I’ll pause the story here to unpack three things I learned from this experience.

One thing that stands out for me is thinking about intersections, or corners. Think about an area that you’re interested in, a skill that you have, and where those two things might possibly meet. I guarantee that you’ll be surprised by the possibilities and that you may very well find a space in which you’d like to work.

The second - and I’ll expand on this later - is that often you only get a sense of what you may want to do by actually doing those things by crafting small, low-risk experiments along the way. One way you might craft an experiment is to simply apply for a job you’re interested in and to see what happens.

Even though that first application to the news agency was an ‘unsuccessful’ interview in terms of linearly-defined outcome (I didn’t get the job), in retrospect it was extremely successful: that experience was so powerful, it pointed me in the direction I was to take next.

Now, for the third extraction from this. I had spent two years at this hedge fund, not doing work that I thought utilised my core competencies. I didn’t spend most of those years writing. Instead, I spent them as an accountant in a back office, working heavily with numbers, spreadsheets, data and technology. I had no idea that all of this would inform what I did next.

But when I eventually joined the same news agency after my Master’s degree, the boss on my team made the decision to hire someone specifically for a job that would leverage all those very skills I’d picked up. So the lesson here is to never discount your experiences. All experience is cumulative.

Like Steve Jobs said - you can only connect the dots looking backward.

At this juncture - entering journalism - is where I was confronted with having to shift my identity.

I was no longer this person who had worked at a hedge fund, but now I had to start acting as a journalist. But here's where things get interesting, because I had a completely different skill set and because I came from completely different background, the usual notions of who or what a journalist is did not apply to me. I still viewed myself as a person who first worked in finance. So, being an outsider, I was able to add value to my job and to my colleagues in a way that was unique and could not be easily replicated. The takeaway here is that we often have skills and experiences that might be useful in a completely different context to the place we may be currently in. So that behooves us to widen our professional horizons and think of ourselves in a much broader sense. All that leads to this idea that our working identity is not fixed.

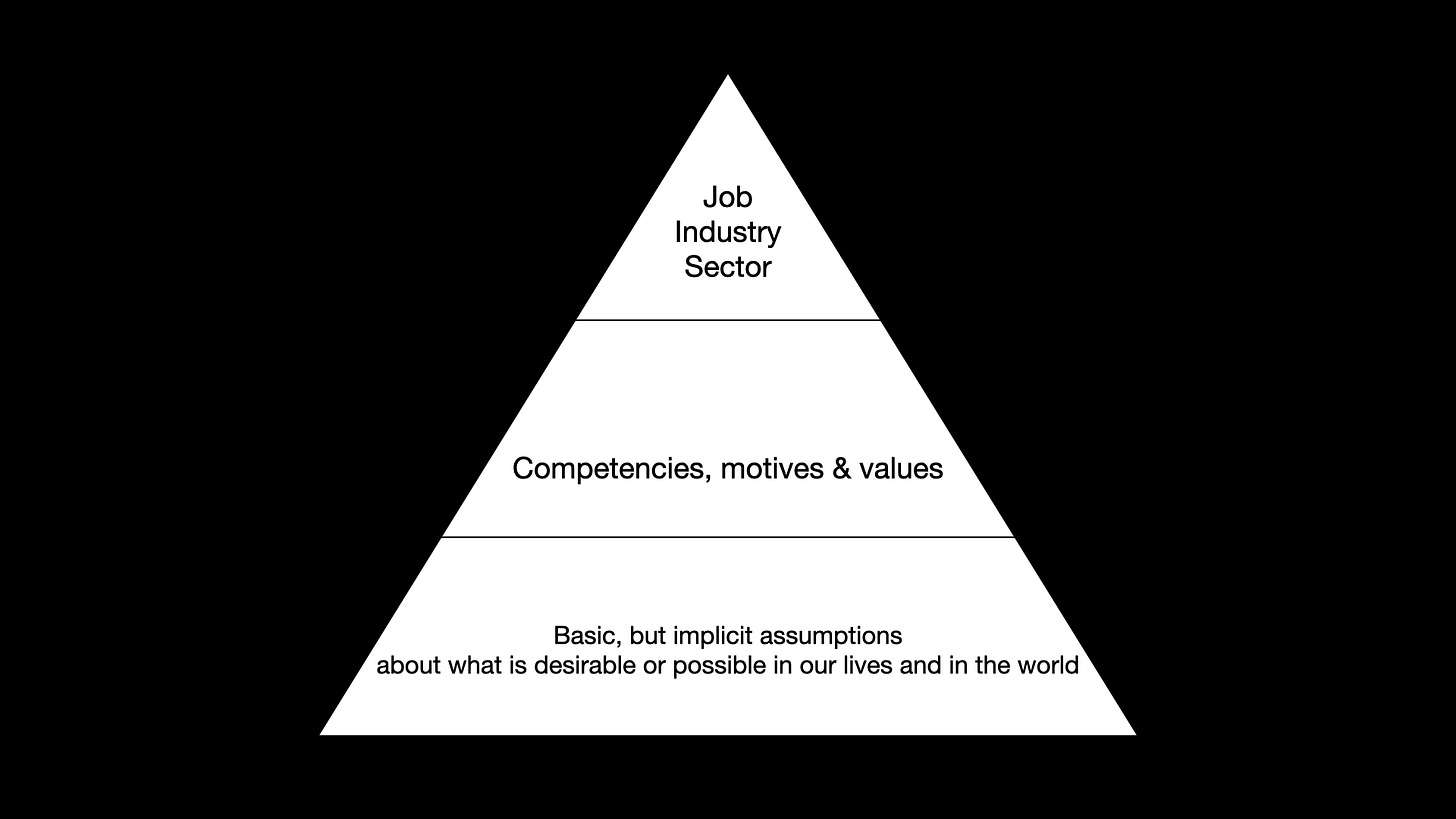

As human beings, we are multifaceted. And we have all these tendencies, needs and wants (tentacles, per Tim Urban) that are often conflicting with each other. And, as a friend said to me recently, our job is often this single domino in front of a thousand others that represent who are. It’s just the visible tip of the iceberg. Our job is not who we are. It's just something we do.

And so how do we bring more of ourselves to our jobs and how do we find jobs that fit and allow us to bring forth the identities that we relate to?

That finally brings me to the last and most recent bit of my career, starting in 2020, where I started to feel that again that I wanted to do something new. I also started to get the distinct sense that I was climbing the wrong hill.

I had not been paying attention to the things happening around me, which meant that a reorganization of my team at work caught me completely off guard. Suddenly, it meant that my boss would change, and that I would be operating in a new hierarchy in which my skills and output were no longer as valued. While I felt disillusionment and discomfort, these were a good thing, because the pain forced me to pay attention again. I began to observe the way the world was changing. Social distancing and the shift to remote work meant the world suddenly converged - even more - on the Internet.

So I began to craft small experiments. I created a website for myself. I did a piece of freelance work and earned my first dollar online. I started a blog and writing more publicly. I started using a new system to document and index information I consumed. And I started a newsletter with my former boss - which eventually turned into the one you’re reading now.

Why were these significant steps? They allowed me to experiment with a new identity - one that was a bit more public, a bit more vulnerable, but also one that was a bit freer and autonomous. Setting up a website set off a domino effect: I began to write and blog about my experiences. I started to observe newer people on the Internet and realised that we’re in a global phase change, playing the Great Online Game. All of these things added up to a newer mode of being, one that manifested even before I began a job search.

And so that brings me to the final point, which is that if you find yourself at the point where you’re looking for a change, often the best solution is to act your way into a new job. This is not easy. But it’s a much more practical path than a plan-and-implement approach.

One way of exploring a new self might just be to apply to jobs and observe how you feel. My experience applying for jobs has been that is it a low-risk, potentially unlimited upside way to assess whether something might be for you or not. If you progress to the interview stage, you’ll be able to talk to somebody new, potentially in an industry or organization you’re not familiar with. If you interview enough times, you’ll start to see interviews as deep, information gathering processes rather than just simple Q&As that one ought to jump through. I’ve had several interviews that never went anywhere, but they proved to be valuable sources of explicit and implicit information about the jobs and industries I was exploring.

Scott Adams, in his book How To Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big, talks about meeting a CEO on a plane who had essentially job-hopped to that position. Every time the guy got a new job, he was already looking for his next one.

“For him, job seeking was not something one did when necessary. It was an ongoing process. This makes perfect sense if you do the math. Chances are the best job for you won't become available at precisely the time you declare yourself ready. Your best bet, he explained, was to alwyas be looking for the better deal. The better deal has its own schedule.”

After several interviews this fall, in a process I can only describe as full of synchronicities, I had to turn down three promising prospects for the job I just took. The better deal had its own schedule.

Thank you!

***

Note: A lot of real-life details have been omitted from this post. As I said, I intended for this to be a story. Linear narratives hide a lot of randomness and details, but serve as a convenient mode of transference for implicit information. I hope my story was useful to you in some way.

Thanks for reading!

Ritvik

Excellent read, Ritvik. Well done. I am excited to see how your career and your life shapes over the next several years.